Courtesy of: Dr. Erica Lombardi, Dietitian Team Astana Premier Tech, and Giacomo Garabello, Fitness Coach and Sport Nutritionist

Summertime for a cyclist should be synonymous with hydration and energy.

The days get longer and you can spend more hours in the saddle under the sun, which increases your energy expenditure and water needs.

However, despite the attention paid to supplementation and nutrition that is now widespread among the majority of cyclists, in these hot months many people remember episodes of muscle cramps following the intake of mineral salts, or even ‘hunger crises’ with sensations such as gastric emptying and empty legs. It is not uncommon for these sensations to occur despite the intake of maltodextrins in water bottles and gels. And so the cause of these episodes is attributed to the poor quality of the dietary supplement consumed.

And yet, if we think of a perfect combination, we can think of the close correlation between the intake of mineral salts and proper hydration, or between the ingestion of maltodextrins and an increase in energy. These factors are undoubtedly interrelated and instrumental in optimising performance and energy sensations in the saddle.

So why did the dreaded muscle cramps occur if mineral salts were taken? And why, in spite of maltodextrins and gels, did you still experience a loss of energy or hunger pangs?

During physical activity, especially under stress, a number of interrelated metabolic mechanisms are at work, involving both the digestive (visceral) and muscular systems, which are also related to the initial state of nutrition and hydration, i.e. before getting on the bike. It is therefore essential to start off hydrated and with reserves of sugars – glycogen.

A supplement taken during physical activity can certainly help performance, but it is difficult to cover any previous conspicuous water or nutritional deficiencies.

In order to make the intake and use of a dietary supplement functional for the benefit of your performance, it is a good rule to follow and bear in mind certain instructions for use:

- The importance of the type of product you choose (individual usefulness and tolerance)

- The personalised quantity (ml/g/h/Kg)

- The method of formulating and temperature of the drink (preparation of the water bottle)

- Programming the most functional time to take it (timing/h)

- The strategic association with other products (liquid rations – flasks and solid rations – bars)

Specifically, the supplement and the bar should always be tested in training and never in competition to test their individual tolerability and the timing with which the metabolism absorbs them. For example, for some products such as the caffeine gel (average ergo effect after about 40′) there may be a different metabolisation process from one cyclist to another. The advice is to try the supplements one at a time to understand the individual and real subjective effects.

The quantity of supplement taken (e.g. 60g/h of maltodextrin), which is recommended for sports people on the label, should be customised by your doctor or nutritionist, who can indicate the quantities to vary according to the type of training or race.

This can be calculated by the nutritionist on the basis of metabolic tests and the history of laf (daily physical activity levels).

Taking a professional’s carbohydrate requirements during the stage as an example, it might be useful to consume 90g/h of carbohydrate or more, but even this amount needs to be ‘trained’: consuming a lot of carbohydrate, even in solid form, requires more oxygen for digestion, which is partly taken away from the muscles.

However, if your real needs are lower than this, consuming excessive quantities, especially in one go (drinking half a bottle or one bottle in a few minutes), as well as causing possible gastric disturbances, will reduce the blood absorption of the product (which if excessively concentrated is not absorbed properly) and therefore its availability in terms of blood sugar and energy for work in the saddle.

If you put a solution in the water bottle that is overly concentrated in sugars of more than 8% and also in salts, the product could turn into a supplement that is no longer functional and energetic, with the opposite effect.

In addition, for a mineral salt and maltodextrin supplement to have a high physiological effect, the fundamental vehicle is water. Care must be taken not to add too much cold water, as this could cause gastric problems. Mineral salts should not be dissolved in over-mineralised water (to avoid the solution becoming over-concentrated), and it is not advisable to take the gels together with the salt bottle, but to carry the absorption with water.

If during an outing you hydrate only with mineral salts and not water, or this ratio is not well balanced, the risk of experiencing cramps is possible and not attributable to the quality of the product.

A good water strategy is to drink in small sips (about 150 ml every 15-20 minutes) during physical activity, alternating if possible, water bottles with a different content of product such as salts or water with maltodextrins (60-90 g/h). This strategy can help to maintain an optimal hydrolitric and energy balance, preventing episodes of cramps or gastric disorders or hunger crises.

However, care must be taken to drink only water to avoid the occurrence of true H20-hyponatremia drunkenness, causing excessive dilution of sodium in the blood, a cation that is easily lost through sweat. The consequences of sports hyponatriemia can be very severe and acute, not only on performance but also on health.

Another condition that should be avoided is swelling the stomach with liquids alone during activity: if the stomach is over-inflated, in addition to gastric problems, you may feel hungrier.

During the outing or race, it is worth taking carbohydrates in solid form, such as an energy bar.

Indeed, chewing sends a satiety signal to the brain, thus avoiding episodes of gastric emptying that could be induced by taking liquid sugars alone.

We have therefore learned that supplementation cannot be taken by chance. In order to bring maximum benefit to performance, it must be strategically planned in terms of quality, combination and timing of intake.

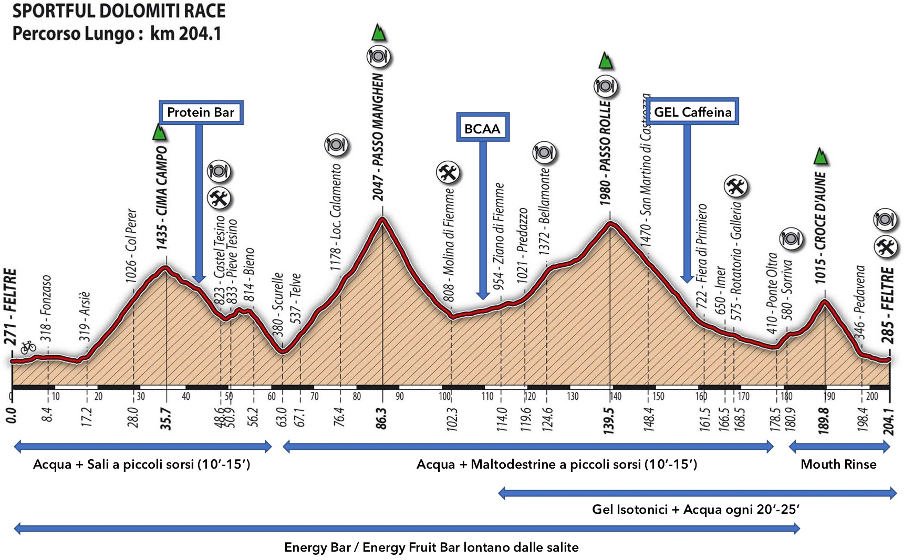

Below is a non-personalised example of a functional water and food SCHEME with liquid and solid rations (minerals, bars, maltodextrins and gels) on a training or competition course. The nutritional strategy must be personalised and worked out by the doctor or nutritionist.

- 1-60° Km water + mineral salts (150 ml every 10-15′ in small sips). You can also take liquid magnesium if you are particularly prone to cramps

- > 60° Km water + maltodextrin (150 ml every 10-15′ in small sips)

- Proteinbar before training/race, Energybar and fruit gels, such as Total Energy Fruit Jelly>, during activity (in small bites every 30′ or so)

- Halfway, shot with BCAA or BCAA NAMEDSPORT> in water bottle or other NAMEDSPORT> with BCCA

- Isotonic gels + water away from the finish line (before and during the climbs alternating with maltodextrin about every 20′ – average of 60g/cho/h)

- Gel with caffeine (about 40′ from the finish)

- Strong Gel> or mouth rinse with maltodextrin.

Example of a nutritional and water protocol for the race which took place on Sunday 29 June.

And how did you feed and integrate?

Burke, L. M., Hawley, J. A., Wong, S. H. S., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2011). Carbohydrates for training and competition. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29 Suppl 1, S17-27.

Jeukendrup, A. (2014). A step towards personalized sports nutrition: Carbohydrate intake during exercise. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44 Suppl 1, S25-33.

Thomas, D. T., Erdman, K. A., & Burke, L. M. (2016). American College of Sports Medicine Joint Position Statement. Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48(3), 543–568.Brietzke, C., Franco-Alvarenga, P. E., Coelho-Júnior, H. J., Silveira, R., Asano, R. Y., & Pires, F. O. (2019). Effects of Carbohydrate Mouth Rinse on Cycling Time Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 49(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-1029-7